Robert Golden

March 2019

first delivered as a talk to students at the

University Sarajevo School of Science and Technology

I’m going to talk about my three linked careers, and the political principals that convinced me to make the decisions I felt were necessary to change one career for another. I want you to understand I am addressing Anglo/American conditions. What they may imply about your own countries is for you to decide.

To begin, let me show you a few images from my first career as a photojournalist.

see video , The Destruction of the English Working Class, and then pause…

In that period I shot many photo-essays, which taught me a lot about storytelling with images. Having previously gone to film school I worked on my essays as if they were films – researching, looking at visual references of photography, films and the fine arts and continually re-storyboarding what I thought I needed to photograph to reveal the underlying truth of my story.

But whilst photographing various commissions I became discontented with the way my pictures were used. The editors and art directors thought, because they paid me, they had the right to construct out of my photographs a different reality acceptable to them and their publishers.

I’d been driven into conflict between my responsibility to my media commissioners and to those who generously gave me access into their lives- something precious and delicate. Ultimately, the misuse of my images by the media forced me to turn away from photojournalism as a way to pay the rent. This led to my second career.

I vowed to continue photographing what I cared about in my own time, while I searched to find what I hoped would be a morally acceptable way to survive.

I made the choice to move as far away as possible from documentary for what would become my day job. I wanted to be in a world I could control rather than respond to. I wanted to be where there was no light until I turned one on.

Instead of using a 35mm Leica I choose to use a 10 x 8 tripod based camera;

instead of the entire chaotic world in front of my lens,

there was nothing until I placed something there.

and I didn’t want that something to be other people.

That meant I choose still-life.

In London’s 1980’s commercial world, because there were so many good photographers, even within still-life one had to specialise in a particular area - as food, cars, stereos and cameras, or jewellery, perfumes and toiletries. Without hesitation I choose food still-life.

Why?

Because in general I do not like ‘things’ except for books.

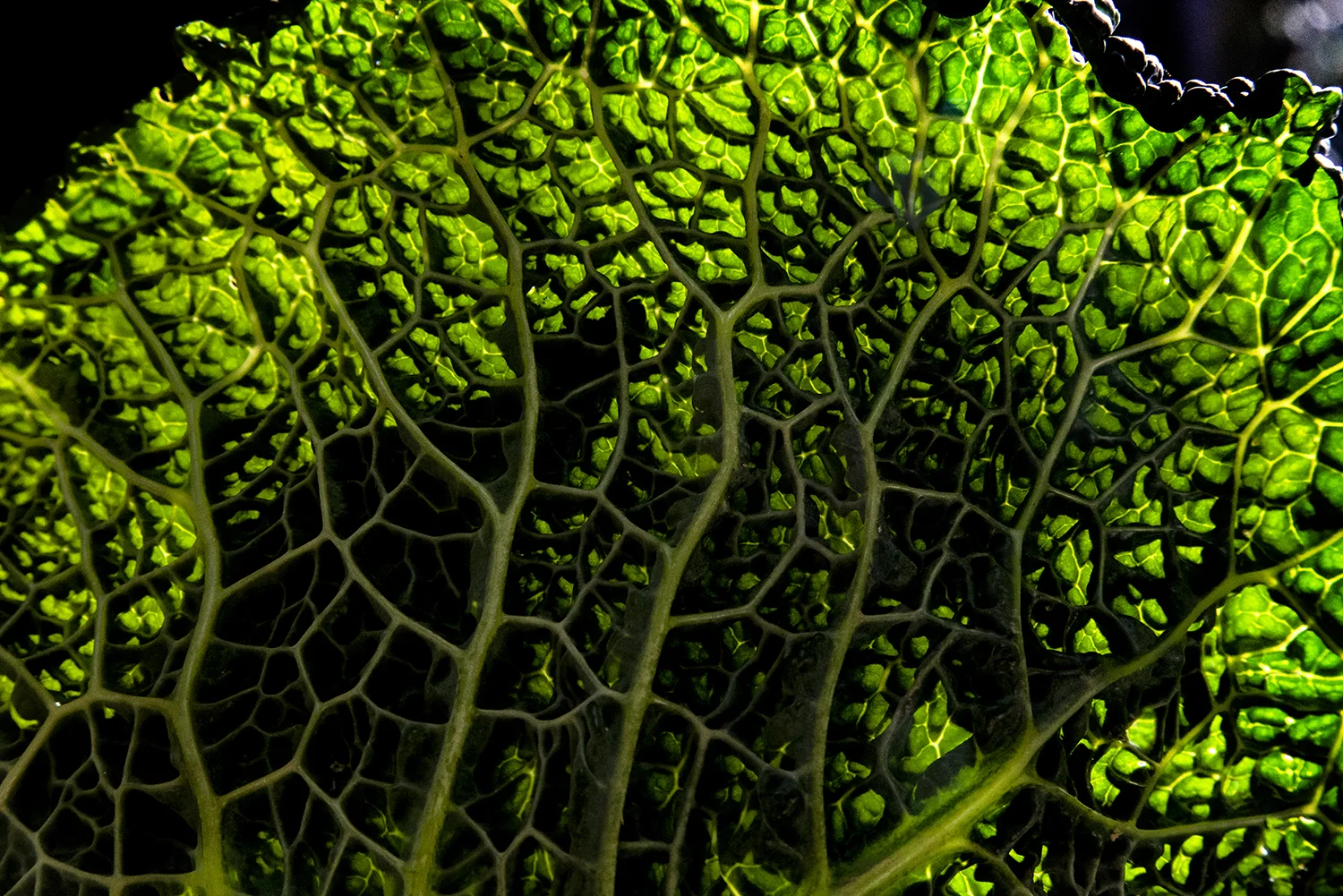

Because fruits and vegetables are themselves beautiful.

Because many stories of food are filled with gifts of caring and sharing,

and because access to food is filled with questions about fair distribution and justice... matters which have always concerned me.

I brought to my still-life work knowledge of art history; and my storytelling from photojournalism meant that instead of creating a self-contained image on what was then the standard white cove background, I made some images as though they were part of a scene being panned across in a documentary film and others that were very graphic – a distillation of my love of the Bauhaus.

To my surprise, I was quickly successful, and was soon asked if I would also light and direct food commercials associated with the print campaigns I was photographing.

see video from above: Still life and liquid commercials shots

In the end I photographed over 30 cookery books, many magazine articles and billboards, and over 900 TV commercials in Britain, Europe and the Middle East.

I won many awards for the ad agencies, and increased the client’s sales with every commercial I made.

But again I started to draw lines in the sand, telling my producer I won’t work for corporations who were causing the development of obesity, degenerative diseases and injuring children’s health. In England I asked why I couldn’t have a black actor in my commercial; in Germany I asked why I couldn’t have a Turkish actor.

These things led to heated disagreements.

I was again shown that moral concerns have no place where profits matter.

During that dawning of my second alienation I never said to myself that my commercial work was worthy or beautiful

because for me beauty is about the soul, not about eye candy;

beauty is about our shared humanity, not about selling hamburgers;

beauty is essential rather than decorative,

and beauty cannot be ordered into existence by bureaucrats and business people.

None the less, in making commercials

I learned a huge amount about film language as how to be precise in showing actions and telling stories.

I learned to cut not to the second, but to the frame,

I came to understand how to capture and reveal an emotion in as few as 15 frames,

how to engender genuine smiles from children

and relevant emotions from adults.

I learned how to translate flowing cream, crunching chips and bubbling liquids into film language that could elicit the feel and smell of these thing

I learned to master the excitement of big close-ups,

high speed filming,

to seduce with colours and tonalities,

In particular I learned the value of how each shot had to advance the story or character development without distraction or deviation.

I also learned about working with crews, actors, agency people and clients. These management skills are an essential part of a director’s tool kit, which is bound up with the nature of leadership, comradeship, caring and also standing your ground creatively and morally.

Having read the Soviet film maker Eisenstein’s Film Form and Film Technique, I learned how to think about one of the key problems in filming – where to place the camera to clearly reveal the story of the scene while also coming to more clearly grasp the emotive qualities of different length lenses in framing subjects.

In that period, as I became successful, I continually wrote film scripts and continued to explore photography.

Finally I left shooting commercials because I had enough of the lying, pomposity and arrogance and because of my need to speak up.

I knew there were stories to tell about how we live and die, about our children and loved ones, about what we value and what we disdain, about the ambiguities of our inner lives and our sense of destiny.

Where were the stories about whom and what creates our wars? Where were the voices protesting against the destruction of the Anglo-American middle and working classes, the closing down of factories, day care centres, libraries, youth services and the terrible injustice of austerity? Where in the popular culture were stories about the hardships of ever increasing economic inequality, where were the viable opposition voices who could sensible offer democratic and just solutions?

We had been numbed into silence, as though the corporate owned popular media had all and everything to say about our lives. This, I knew, was not true. We have more perceptive things to say to each other then do they to us; because our feet are on the ground amongst those we know and love we have more humble, more meaningful things to say to each other, but there are very few who are willing to say them.

It was therefore in my hands to choose to speak up or not; to make films of unity or films of conformity.

I returned to my first love, documentary, but using moving images rather than stills. I had begun to understand that films do not reveal a social/historical moment as reality, they instead are research into existence. They says, ‘At that moment, in that place, that light reflected from that surface’. Beyond that, most of what happens is a consequence of energy, presence, commitment and creativity the film-maker brings to the event and then how the filmed event and its viewers interact.

To repeat: good films do not report on history so much as they research existence. They ask questions and prompt viewers to reflect on their lives.

Since then I’ve made – as an independent –over 40 documentaries seen around the world by millions of people.

Here are few excerpts from some of them.

See video from above: Documentary Fragments

Film, perhaps as no other medium, has the ability to transport us to places and people we previously had no idea about, and to transform those characters into flesh and blood human beings: whom we may come to care about and wish the best for.

In that way film has the power to humanize our world, to help overcome the generalizations of ‘other’ races, ‘other’ religious groups, ‘other’ genders.

For film-makers to cross the chasm between themselves and an audience requires many skills, knowledge, experience and a whole lot of bravery to accept failure as part of the learning process. Kurosawa said, to become an accomplished film-maker you must first make 7 films.

Making a long form film is a bit like herding amoeba. To make a long form film you must develop ways to understand the many things you need to know.

One way to do this is to recognise the different concerns mediated by form, content and technique.

They are distinctive areas of knowledge and creativity, which overlap. The easiest of these to master is technique.

Technique is the knowledge and control of the mechanical, optical, chemical, photo-electrical and software tools. It needs to be mastered for film-makers to have creative control over their vision. Technique in itself is based in engineering, maths and science-based knowledge: it is how it is used which may be creative.

Without it you are at a loss to make anything of value; but with mastering technique new horizons continually offer themselves. And this question of technique also applies itself, in psychological terms when directing actors.

...

I’ve learned more about film-making language in the edit suite than anywhere else.

For instance:

It’s where the success and failures of my story boarding become clear,

its where I realised I had not shot decent cut-aways to allow me to get out of an action or dialogue;

and where I realised that my edit was visually boring because I had only framed mid-shots in a dialogue scene.

more importantly, I learned about rhythm – within dialogue, actions, movements and within scenes as well as within and between acts. As with knowing where to place the camera, coming to appreciate and use rhythm is central to good film-making.

While making commercials I travelled a lot, sometimes almost constantly. Often I had an opportunity to speak with the young assistants - those eager, underpaid film students.

I’d ask them what they did to increase their knowledge. What they were doing was hoping for a break – what they weren’t doing was making films.

I would suggest that as they probably has some sort of camera - if nothing else a phone camera,

that they could access a free online edit package,

that they were surrounded by friends who wanted to be a DoP, an actress, a set designer,

they could get together, make stories and shoot them.

It could cost nothing but time. And believe me, they as you will encounter a steep and rich technical and formal learning curve as did I when making those endless commercials.

Theory and History are vital but ‘Making’ is where you develop your vision as an artist. Remember Kurosawa.

We have three basic materials to work with: TIME in unity with SOUND and LIGHT. Time and sound exist without film but there is no film without light: remember ‘photography’ means ‘writing with light’.

Light is not just functional illumination, it is evocation - it fills the screen with meaningful beauty- it transforms the mundane into romance, threat, doom. It fills the screen with meaning that no words can elicit. To not fully engage with light in cinema is to turn your back on your most powerful storytelling ally.

This brings up the question of visual literacy - which is indispensible for a film-maker. This literacy aids you in pre-visualizing your film, which is the ability to imagine something that does not yet exist.

To develop pre-visualization through visual literacy you of course need to look at paintings, read poetry, look at the masters of photography and watch films - not just those made since you were born, but well into the history of the medium. An inquiry into the history helps you to avoid reinventing the wheel while enjoying great beauty and filling you with ideas.

You may know that since the Renaissance young painters have sought out the paintings of previous masters and copied them to come to understand how the masters did what they did.

From the age of 13, I tried to copy what I saw in the great photographer’s work. It is not that I am a clone of Paul Strand or W Eugene Smith but they, as Eisenstein, Chris Marker and others, have informed what I know and who I am. They become a part of your vocabulary, redefined by who you are.

Once you begin to use light and time and its rhythms to create form, you enter the un-measureable subjective arena of creativity, experimentation and things beyond the rational – as is art.

...

I’ve talked a little about technique, now I want to speak for a moment about Form and Content.

Form pervades the entire being of a film: the composition of each frame, the temporal and spatial relationships between characters and events, also the graphic relationship of shot to shot, the structure of the scene, the structure of scene to scene in the act and the structure of act to act.

Form defines the physical aspects of objects; it’s the architecture in which the content is presented.

Content is the reason for the form to exist; form and content together create beauty.

But be aware: Well-structured form without meaningful content is decorative if not to say, decadent; meaningful content without well-structured form is often weak.

This invariably leads to the question: What are the reasons you wish to make films? When you answer that, you begin to recognise possible content and its storytelling and you may also recognise if you wish to become an entertainer for the status quo or you’d rather contribute in a meaningful way to the well being of your fellow humans in our shared world?

Do you want to make films of unity – those that serve the future or films of conformity – those that serve the present and past?

In my life, I cannot claim there was any social value in the commercial work I’ve done. I only see value in my self-inspired independent projects.

For me, working on my own projects is about truth telling.

Its about revealing stories that are in various ways essential to social and/or personal ideas of existence - which may give hope to others in their isolation -

This isolation has been purposely fostered by the now 40 year old Anglo-American neoliberal desire to replace ‘we’ with ‘me’,

to have us self-define ourselves as ‘consumers’ not ‘producers’

and to replace the commonality of our collective history with the individuality of psychology, all in order to do what?

Through corporate media’s over-sexualised, infantilized empty culture that would lure us away from collectivist ideals of the 1960’s, they wish to atomize us; to separate one from the rest.

This has created a more lonely, harsher world. For those who decide to serve the corporate media, they enter a dreamless state incapable of being filled by their rewards of wealth and fame.

Whatever we think the needs of our souls may be, their attempt to replace those needs with greed and crass materialism has gutted our world of any meaningful sense of society, collaboration, civic responsibility and service to humanity. Is it any wonder so many people are lonely, lost and confused?

All truth telling is of course based on some notion of what truth is. For the film-maker to understand the true complexity of human nature to be able to create believable characters, he or she needs to recognise there are simultaneous but contradictory truths within society and within most of us. To allow for those, is to embrace democratic pluralism rather than the singular demanding voice of totalitarianism.

Art is complex, multidimensional, questioning and creates a dialogue between the artist and the audience...this dialogue is about life as it is and it moves from the specific to the general, that is, from the everyday to the universal.

On the other hand, popular culture is simplistic, single dimensional, unquestioning and creates a monologue. Within its monologue, popular culture is more akin to propaganda, which in essence does not question but insists the citizen accepts its assumptions.

It employs spectacle, sex and violence to paper over the dark valley that separates most people’s recognisable reality from the enforced reality of the harmful hollow popular culture.

Harmful?

• It convinces people that the present system is the only possible system,

• It convinces people that reality is what they tell people it is,

rather than what people’s instincts tell them it is,

• It convinces people that worthy art is what they, the neoliberal elites and their politicians admire – a banal entertainment that asks few questions but which underlines the elite’s moral authority - rather than a truer art created by difficult, questioning people who do not make films for fame and fortune, but to embrace what the Czech playwright and revolutionary, Vaclav Havel wrote, “When a truth is not given complete freedom, freedom is not complete.”

To me this need to live within the Complete Freedom Of Truth is what I care about: that in my life I know I need truth, beauty, love and knowledge and that the more beautiful and humane the images and sounds I can offer and the more questioning the piece, the more I may connect my viewers with my film’s content.

This is about creating a sound and image equivalent to my meta-story: that too many human beings are in struggle against economic bullies, and against bureaucratic and political thugs, and that many of those in struggle possess dignity and untold strengths and even as they are forced to carry unacceptable burdens they do so with grace; a grace not possessed by politicians and corporations, those who own the cultures and societies we build with our labour.

So indeed, it became clear to me in my third career that I had to decide if I would rather create films of unity to serve the future or films of conformity to serve our dark present and past?

...

REFERENCES

ART MOVEMENTS:

The Bauhaus, New Objectivity (in German: Neue Sachlichkeit)

FILMS and FILM MAKERS:

Sergi Eisenstein’s books Film Form and Film Technique

films: Battle Ship Potemkin,

Ozu’s Toyko Story

Kurosawa: any film made by him but of course The Seven Samurai and Jojimbo

Chris Marker: La Jette, Sans Soleil

Barry Jenkins: Beale Street, Moonlight

the Italian neo-realists and especially De Sica’s Bicycle Thief,

the French Nouvelle Vague film makers and especially Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie,

recent films: The Mud People, The Green Book,

photographers: Paul Strand; W Eugene Smith, Robert Capa, Edward Weston

WRITERS/PHILOSOPHERS:

Vaclav Havel, Albert Camus esp The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, anything by John Berger

POETS:

Garcia Lorca, Nazim Hikmet,

PAINTERS: Caravaggio, Jackson Pollock, Ricky Romain